Sustainable development in the 21st century

Wayfinder is informed by a set of core insights about the sustainable development challenge that humanity faces today: We now live in the Anthropocene where humans have become the major force of change on Earth. In this new era, we need to find development trajectories that stay within critical planetary boundaries while at the same time meeting the needs and rights of people. This can only happen through a biosphere-based approach to development that reconnects people to ecosystems, that make us stewards of planet Earth, and that fosters reciprocity between people near and far.

We live in a complex and rapidly changing world

We live in a time of increasing complexity and rapid change. Our globalized world is becoming hyper-connected, and we face challenges of political turbulence and financial instability, but also accelerating climate change and increased pressures on natural resources such as fisheries, forests and freshwater. A growing body of scientific evidence suggests that we have moved into a new geological era: the Anthropocene, or the age of humans1. In the Anthropocene, humans are the largest force of change on the planet. This should not be confused with our ability to steer the development ahead of us, which due to interactions and feedbacks of the Earth System, has its limits.

In this new era, everyone is, figuratively speaking, in each other’s backyard, and social and ecological changes in one part of the world have the potential to rapidly cascade across geographic scales, often with surprising impacts in distant regions2. For example, the 2007-2008 global food price crisis showed how complex patterns of global trade, agricultural production and oil prices can lead to food insecurity and social unrest in places as far from each other as Haiti, Egypt and Bangladesh. This reality of uncertainty rather than predictability, and abrupt change rather than stability, has profound implications for how we govern our societies and ecosystems. In the 21st century, all local prospects for development are affected by processes at regional and global scales. Similarly, local actions aggregate up and generate effects far beyond where they originated.

Click here to hear more on the Anthropocene from Johan Rockström, Former Director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Identifying sustainable, safe and just trajectories

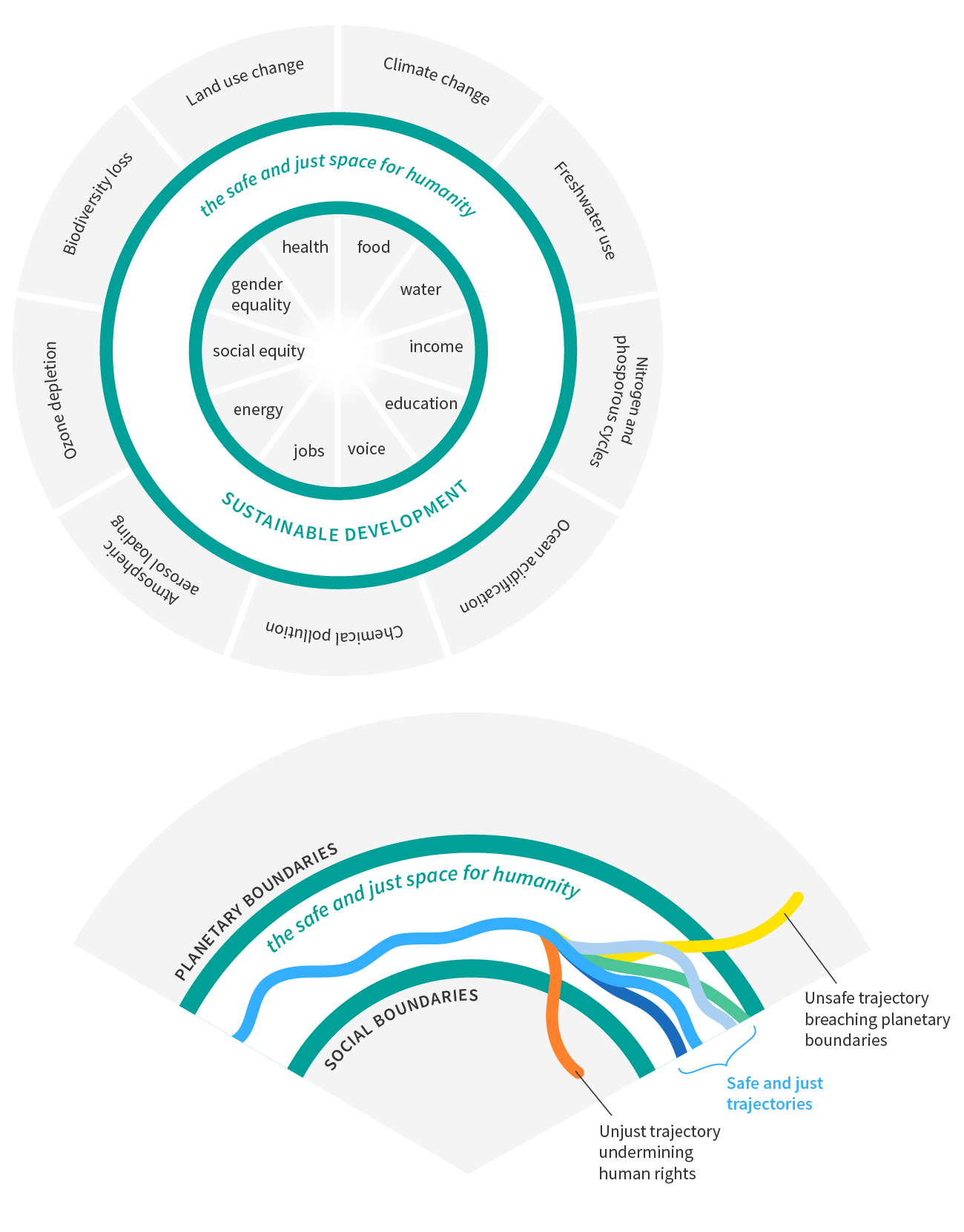

Human activities have reached a scale where they affect vital planetary processes. Scientists have identified nine global biophysical limits or “planetary boundaries” that are critical to maintaining the long-term functioning of the Earth3,4. Four of these limits (climate change, biodiversity, land system change, and altered nitrogen and phosphorus cycles), have already been crossed. While the planetary boundaries can be seen as an environmental ceiling for human activity, we also need to ensure just and equitable development, whereby each person on the planet has the ability to meet their human rights, including health, equality, and choice5. These limits have been referred to as social boundaries, or the social floor upon which development must stand.

Combining the social and ecological/biophysical boundaries creates a doughnut-shaped space (figure 1, top) within which humanity can thrive6. Only within this space is development that is both safe and just possible. This is what we in Wayfinder refer to as sustainable development. Within this so-called doughnut, multiple trajectories of development are possible. These will, to varying degree, contribute to maintaining or improving the capacity of the biosphere and be more or less aligned with the needs, values and aspirations of different groups of people (figure 1, bottom). The purpose of Wayfinder is not to define a single future trajectory, but rather to explore the range of possible trajectories that fall within this sustainable, safe and just space.

Figure 1. Top: Scientists have identified nine critical biophysical planetary boundaries, beyond which the Earth system might start to function radically different (plotted on the outer circle in the figure). In addition to these boundaries, there are also social boundaries that needs to be respected, ensuring that each person has the ability to meet their human rights, including health, equality, and choice (plotted on the inner circle). Combining biophysical and the social boundaries creates a doughnut-shaped space within which humanity can thrive. Bottom: Only within this so-called doughnut, sustainable development can take place. Multiple trajectories of development are possible in this space, that to varying degrees contribute to the productive capacity of the biosphere and that more or less align with the needs, values and aspirations of different groups of people. Illustration: E.Wikander/Azote, adapted from Rawarth (2012) “A safe and just space for humanity: Can we live within the doughnut?” discussion paper, Oxfam, and World Social Science report (2013), “Changing Global Environments”.

While the planetary boundaries apply at the global scale, and the social boundaries apply at an individual level, it is critical to reflect on what these concepts mean for sustainability work at local to regional levels as well. Although the global sustainability problems that that we face today manifest themselves in different ways and to varying extent in different places around the world, it is important to realize that how we choose to deal with these issues now matters. Both because our choices have immediate equity effects, as many people still suffer from poverty and marginalization, and because local actions aggregate up, and at the macro-level there is nothing relative about the sustainability challenge – we only have one planet.

Click here to learn more about Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth, Visiting Senior Research Associate at the Environmental Change Institute at Oxford University.

A biosphere-based approach to development

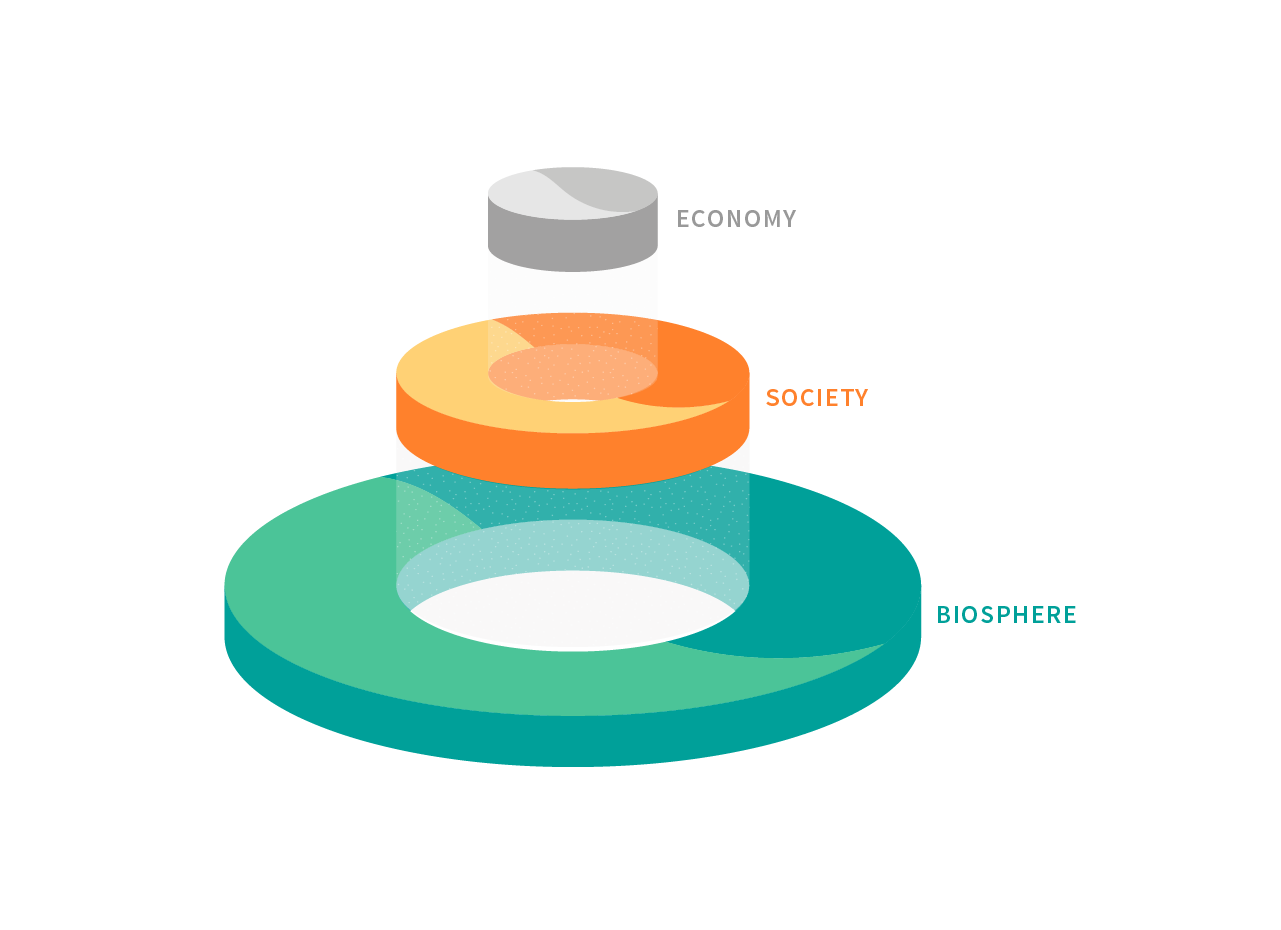

The biosphere is the thin layer surrounding our planet that supports all life on Earth. The biosphere is home to societies, in which our economies are embedded (figure 2). This means that there are no people without the need, directly or indirectly, for ecosystems and the services they provide. For example, urban dwellers who may have no direct interaction with nature, still rely on food and other resources from ecosystems. In the Anthropocene, the reverse is also true, meaning that there are almost no ecosystems on the planet that are not shaped by people. Even the most remote coral atoll is affected in some way by climate change, global shipping routes and microplastics.

Figure 2. The biosphere is the foundation which human prosperity ultimately rests on. The biosphere is home to our societies, which embed our economies. Illustration: E.Wikander/Azote, adapted from Folke et al. (2016)

A prerequisite for sustainable development in the 21st century is an integrated social-ecological systems perspective that recognizes nature’s fundamental contribution to our well-being, socially and economically7,8. Without this, we will not be able to stay within critical biophysical and social boundaries. This perspective differs fundamentally from the worldview that currently dominates public debates, where human progress and economic growth often are seen as disconnected from the biosphere, and where people and nature are treated as separate entities.

Wayfinder emphasizes the necessity of a biosphere-based approach to development, where we become stewards of our planet9, as this is the only chance for roughly nine billion people to peacefully co-exist on this planet. Equally important will be to foster a sense of reciprocity between people near and far, so that sustainable, safe and just futures will be a real possibility for all humans.

Click here to learn more about the biosphere by Carl Folke, Science Director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Click here to learn more about a new context for development by Belinda Reyers, Former Director of the GRAID programme at the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Resilience thinking – a lens that helps us understand the sustainability challenge

The resilience concept has rapidly gained popularity in science, policy and practice over the past decades. It is now frequently referred to in various professional communities including the international development sector (often relating to household economics), environmental policy (especially regarding disaster risk reduction), engineering and psychology. Each of these communities has their own understanding of what resilience means. It is not our objective to resolve these conceptual debates, but to avoid confusion we explain here how social-ecological resilience thinking forms the basis for this guide and why this lens is useful for approaching the sustainability challenges that we face today.

To start with, Wayfinder is based on a very broad understanding of resilience as being not only a system’s property but also a way of thinking – resilience thinking10. Rather than a coherent theory, this is a collection of ideas and analytical perspectives that have their roots in complexity science and social-ecological systems research, which over the past decade has emerged as a frontier of sustainability science. This is a forward-looking take on resilience that goes beyond the coping focused definitions that dominate current development debates. Resilience thinking, as applied in this guide, deals with how complex social-ecological systems (that consist of people embedded in a landscape, which they experience, depend on, manage and extract resources from) develops dynamically over time in the face of change, through processes of adaptation and transformation11.

The focus here is thus on social-ecological systems. These complex systems are difficult to manage for a variety of reasons. First, change rather than stability is the norm. Shocks, such as droughts or market fluctuations, cannot always be predicted, nor the timing and magnitude of such events. Furthermore, in complex systems there are few obvious relationships between cause and effect. This leads to emergent outcomes, or in other words, outcomes that could not have been easily predicted. It is difficult to understand what causes change and which levers to pull to create desired change without creating other unintended changes. Because of unforeseen consequences, there are many examples where organizations acting with the best of intentions intervening in a community have actually reduced peoples wellbeing.

Yet another challenge related to the management of complex systems is that change is often non-linear12. Gradual change often accumulates over time, such as the deterioration of soil health or the evolution of cultural traditions. These slowly changing dynamics tend to go unnoticed, but eventually they may reach a tipping point, leading to rapid and sometimes irreversible change in how a system behaves. In social-ecological systems, this type of ‘regime shift’ often influence how people benefit from and interact with their environment.

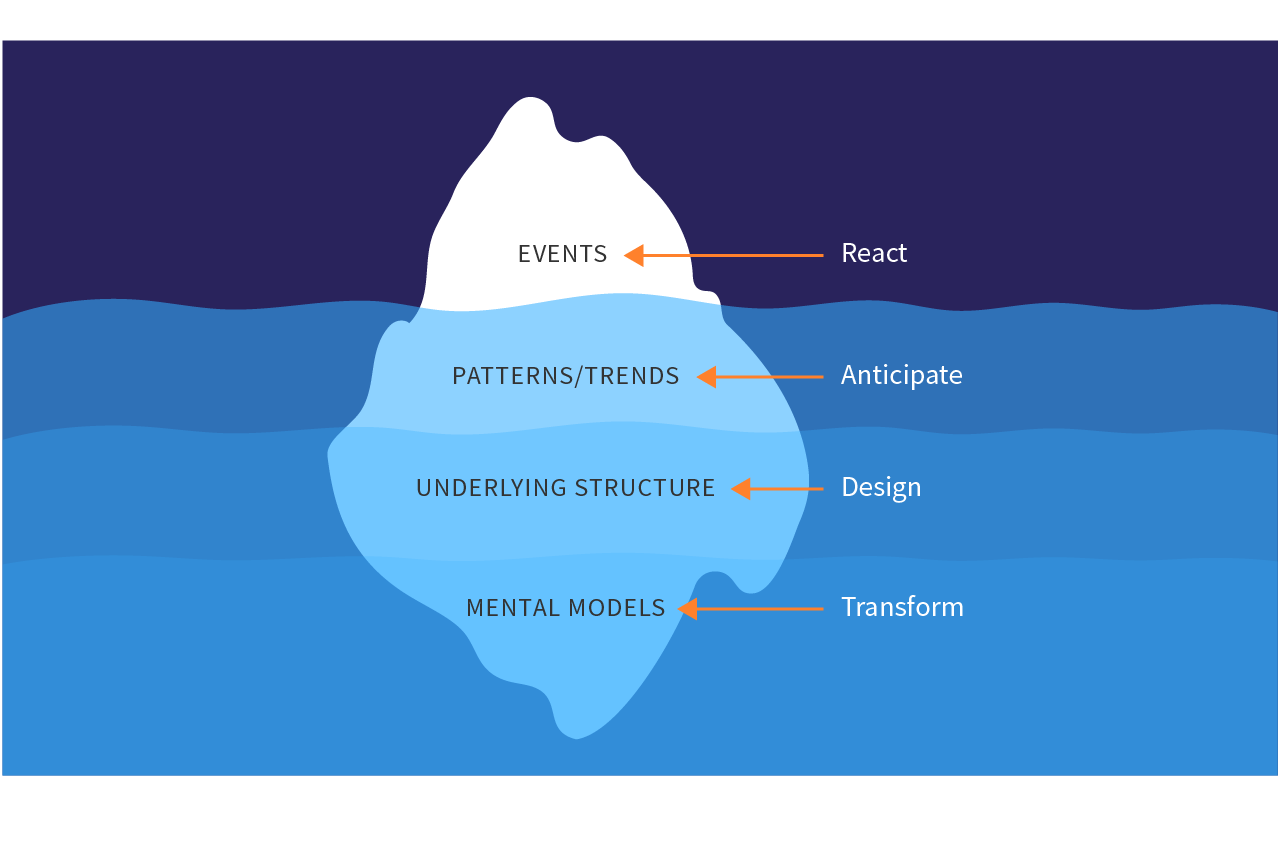

Figure 3. Resilience thinking helps us look below the surface of events and rather than just treating the symptoms, also identifying the root causes of sustainability challenges we face. This enables us to actively navigate change rather than just reacting to it. Illustration: E.Wikander/Azote, adapted from Goodman (1997), “ Systems thinking: what, why, when, where and how?”.

During the past half-century, dominant management strategies have tended to emphasize efficiency and focus on command and control approaches such as maximizing yields of select resources. In this endeavour, proposed solutions have often treated symptoms rather than root problems. Disturbances may have been prevented, but often at the cost of increased vulnerability as a result. The complexity of linked social-ecological systems has been neglected, and people have generally assumed that change would be linear, predictable and reversible. These assumptions have brought with them significant costs, particularly in terms of declining ecosystem services.

A new approach to navigate social-ecological systems towards sustainable, safe and just trajectories, requires strategies that are flexible enough to deal with variability, that considers the complexity of cross-scale and cross-sectoral linkages in the Anthropocene, and that emphasizes active learning. Resilience thinking embeds all of these characteristics, looking below the ‘surface of events’ to identify root causes of the problems that we face and deep leverage points that can fundamentally change system dynamics and redirect development towards more sustainable futures (figure 3). This perspective enables us to actively navigate change, rather than just reacting to it.

Click here to learn more about resilience thinking by Carl Folke, Science Director at the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Click here to learn about resilience thinking in practice by Paul Ryan, Resilience Practitioner with the GRAID programme at the Stockholm Resilience Centre and Garry Peterson, Professor at the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Key references

1. Crutzen, P, J. 2002. “Geology of mankind.” Nature 415.6867 (2002): 23.

2. Liu. J. et al. 2013. Framing sustainability in a telecoupled world. Ecology and society 18(2):26

3. Rockström, J, et al. 2009 “Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity.” Ecology and society 14.2 (2009).

4. Steffen, W., et al. 2015 “Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet.” Science 347.6223 (2015): 1259855.

5. Raworth, K. 2012 “A safe and just space for humanity: can we live within the doughnut.” Oxfam Policy and Practice: Climate Change and Resilience 8.1 (2012): 1-26.

6. Leach, M., et al. 2013 “Between social and planetary boundaries: Navigating pathways in the safe and just space for humanity.” World social science report 2013 (2013): 84-89.

7. Folke, C., et al 2011. “Reconnecting to the biosphere.” AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 40.7: 719-738.

8. Folke, C., et al. 2016 “Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science.” Ecology and Society 21.3

9. Chapin S., et al. “Ecosystem stewardship: sustainability strategies for a rapidly changing planet.” Trends in ecology & evolution 25.4 (2010): 241-249.

10. Walker, B., and D Salt 2006. Resilience thinking: sustaining ecosystems and people in a changing world. Island Press

11. Folke, C., et al. 2010 “Resilience thinking: integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability.” Ecology and society 15.4 (2010).

12. Scheffer, M. 2009 Critical transitions in nature and society. Princeton University Press.