Creating a ‘

Change Narrative’ rather than a ‘Theory of Change’

Before engaging the wider community in this work it is worth spending some time in the coalition to reflect on how you think the Wayfinder process will contribute to creating a more sustainable trajectory for your system.

This is the very first step in developing what we call a “Change Narrative”. We use this term on purpose, and you should not see this as a “theory of change” (see box 8.1), but rather as a developing hypothesis. The Change Narrative is a synthesis of your current understanding of how systemic change may be achieved in your system. It takes the shape of a simplified story that considers the inherent complexity and uncertainty of

social-ecological systems.

This story is central to Wayfinder. It will evolve greatly throughout the 5 phases, as new knowledge is generated and your collective understanding of the

system dynamics deepens. In the end, the Change Narrative will be concrete and plausible enough to take the form of a strategic Action Plan that can be tested in reality.

Before engaging with a broader group of stakeholders, it is important to reflect on the type of change that you hope to achieve through the Wayfinder process, and how you believe this change will happen. Why will the Wayfinder process be different? This is the very first step in developing your Change Narrative. Photo: iStock.

Change Narrative components

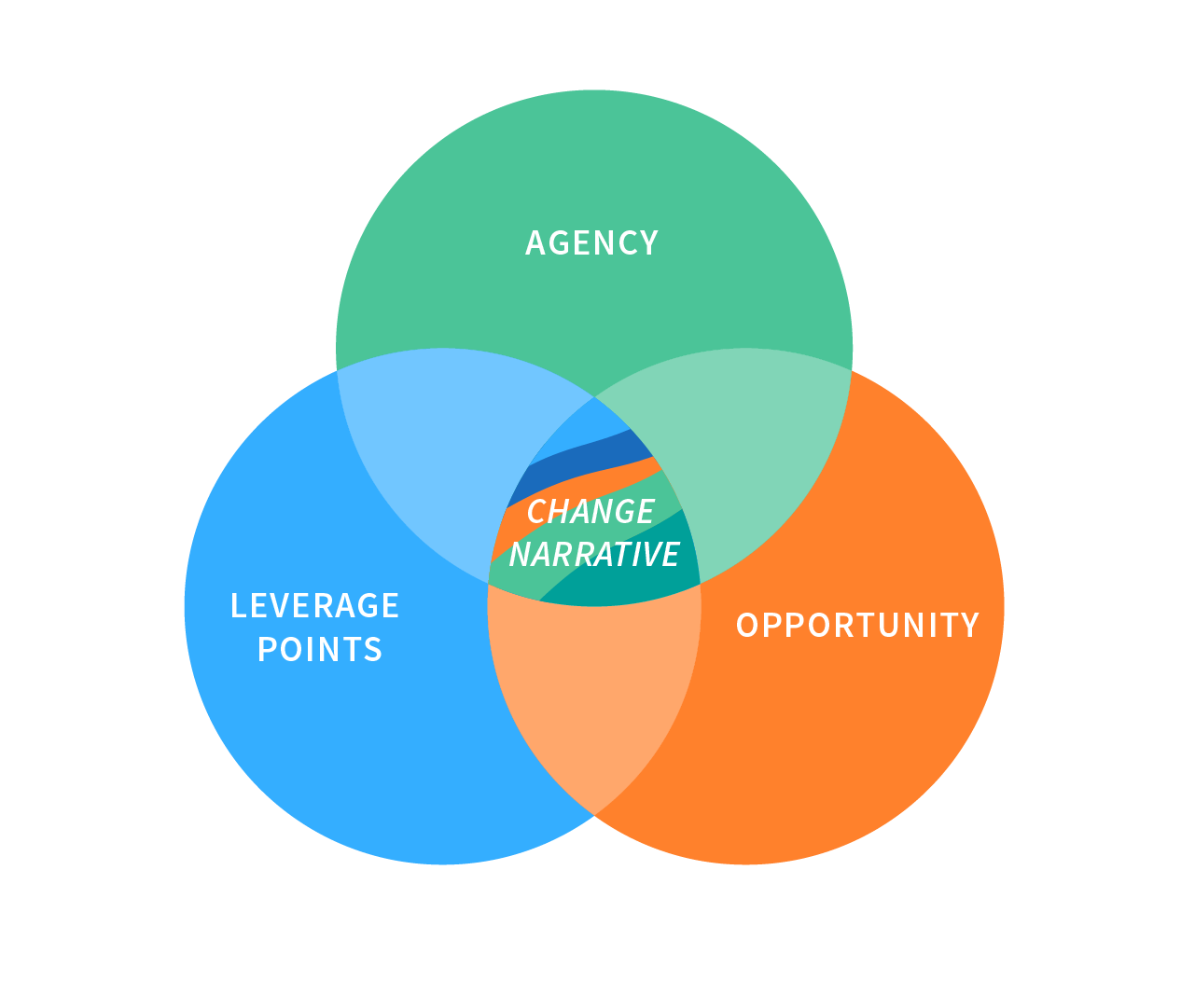

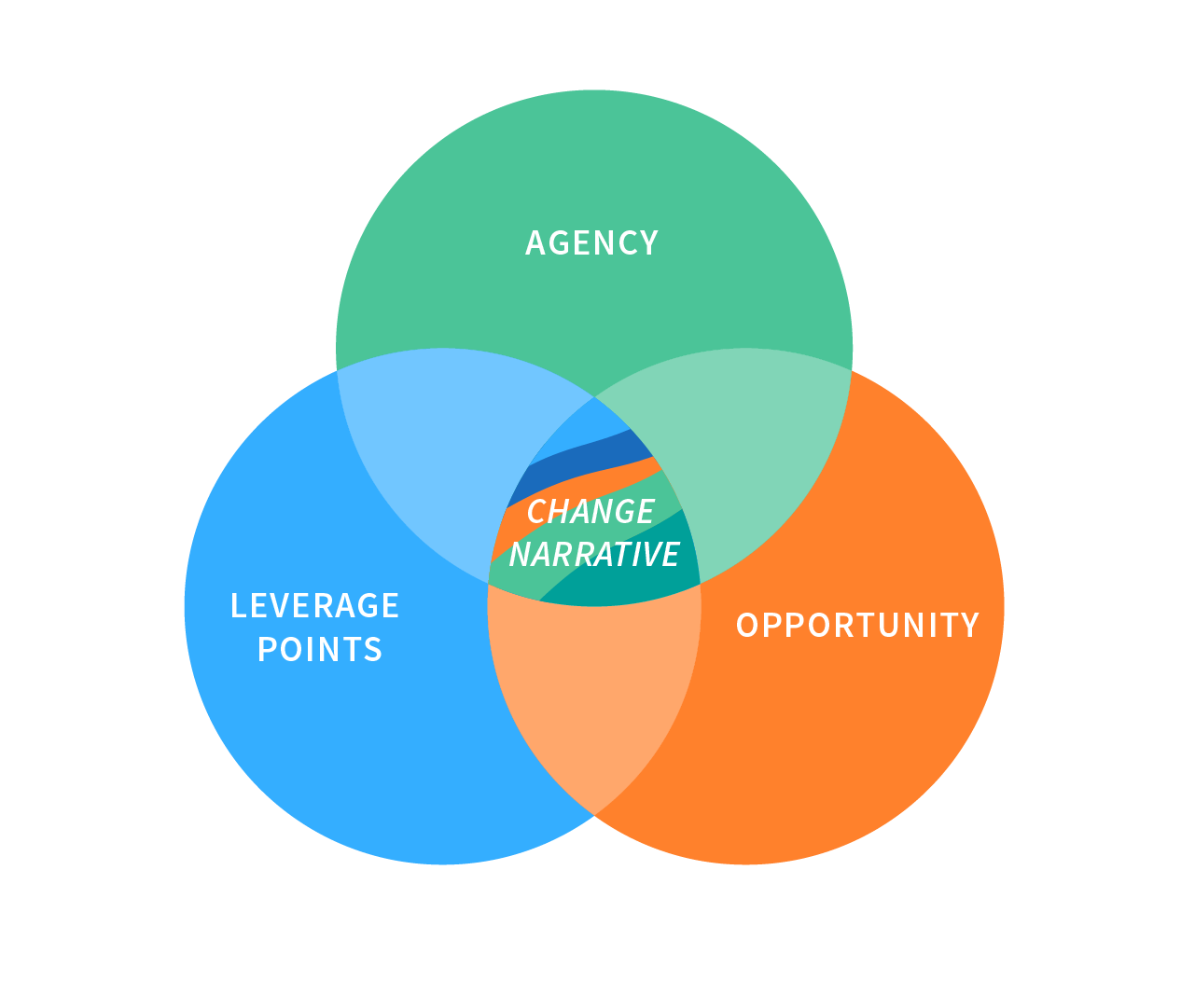

Very briefly, the Change Narrative in Wayfinder has three key components (figure 8.1). The first component is

leverage points for systemic change, which are locations in the system dynamics whereby a small intervention has the capacity to influence the system behavior substantially. The second component is

agency, which refers to who has the capacity to influence those leverage points. The third component is the overall

opportunity context for making change happen, which consists of existing social and institutional structures in which we, as actors, are embedded, and which may hinder or facilitate different kinds of change.

Figure 8.1. The Wayfinder Change Narrative has three components: leverage points for systemic change, agency, and opportunity context. Leverage points refer to places in the system whereby a small change has a substantial influence on system behavior. Agency refers who has the capacity to influence those leverage points. Opportunity refers to the overall context of factors that may enable or hinder change in a system at any given point in time. The Change Narrative is a “storied” account of how change may happen in your system that considers these three issues. Illustration: E.Wikander/Azote

We will come back to this with a lot more detail later on in this guide, but at this stage it is useful to have a first discussion in the coalition (see attached discussion guide) about how you believe that change generally happens in your system, how you think the Wayfinder process may contribute in creating change, and reflect on how you in the coalition are positioned in relation to the system that you are trying to change, i.e. your sphere of influence (figure 8.2). Reflecting on these issues now informs the expectations on the process and enables you to be strategic about how to design the process. It also gives the process its very first, overarching framing.

Figure 8.2. The extent to which the Wayfinder process will be able to contribute to change in the targeted system, depends on where the Wayfinder process is situated in relation to that system. Reflecting on your own position and sphere of influence, in relation to where important decisions are made that shapes the system’s future, is therefore important. Illustration: E.Wikander/Azote

Box 8.1 – Change Narrative vs Theory of Change

In Wayfinder we work with a “Change Narrative” instead of the traditional “theory of change” concept that is commonly used to inform development programs and projects. The Wayfinder approach is not compatible with conventional theories of change for two main reasons.

First, in practice conventional theories of change tend to assume a linear cause and effect model of change, which does not match with the complexity perspective that underpins Wayfinder. Trying to create change in

complex systems will produce both intended and

unintended consequences. Small-scale experiments can help reduce uncertainty, but in these types of systems, some level of uncertainty will always remain. Therefore, the inputs, outputs, outcomes logic that are often reflected in conventional theories of change do not work when dealing with sustainability issues in social-ecological systems.

Second, “theory of change” often implies a single way forward in contrast to multiple future trajectories and the notion of strategically navigating within sustainable and just boundaries and improving

option space over time, which is the focus of Wayfinder. As an alternative, we use the concept change narrative, which we see as a more dynamic representation of how you believe change might happen in your system, focusing on systemic leverage points for change, the agency to influence those leverage points, and the overall opportunity context for making change happen.