Ask at least 5 whys

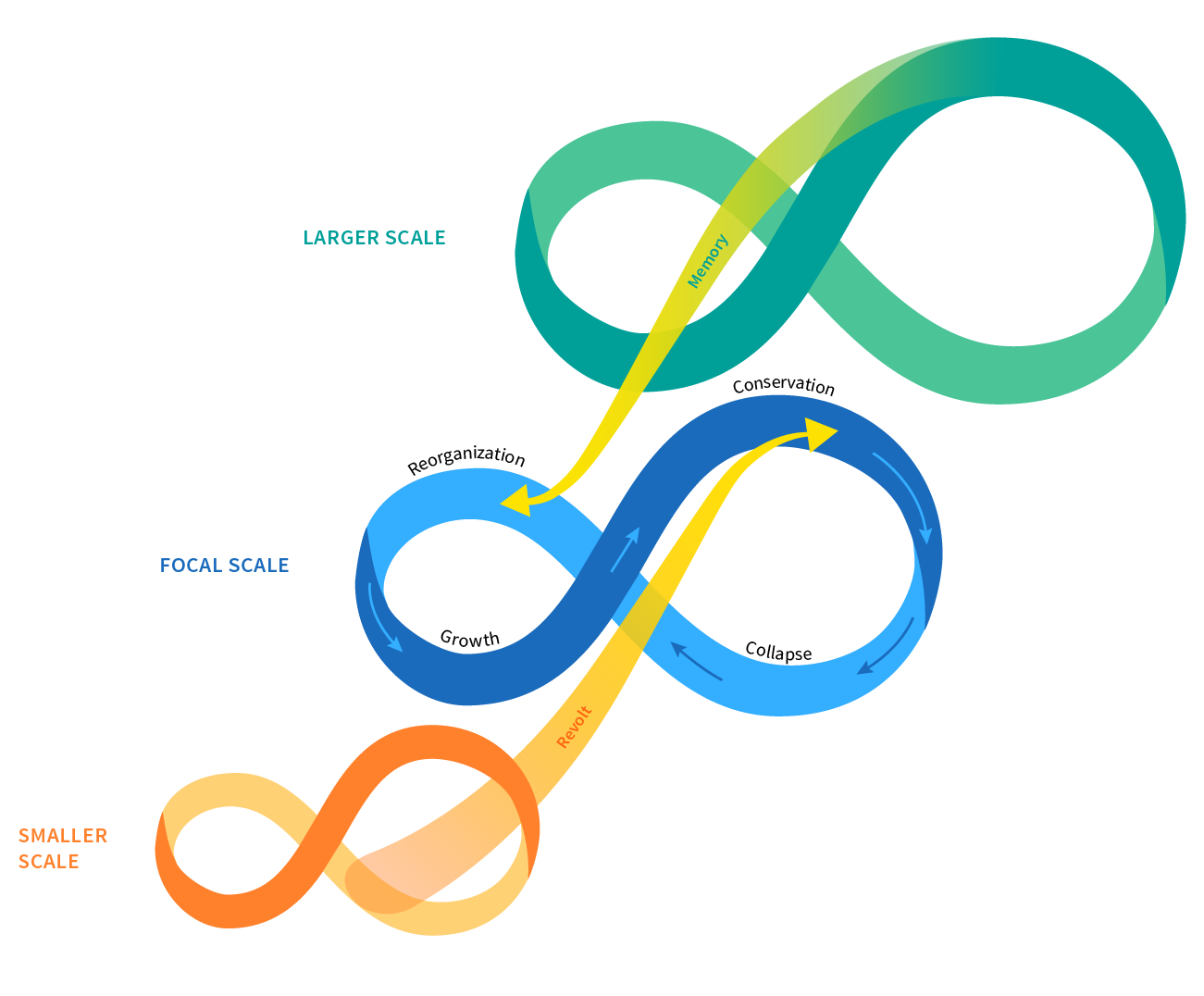

There is no one correct way of approaching the question, “how does this system work?”. Exploring the relationships between key system variables that govern a system’s behavior can be done in many different ways. Our advice is to start by qualitatively focusing in on the more slowly changing system variables ( controlling variables), on potential thresholds and on key feedbacks.

Exploring system dynamics is the core technical element of Wayfinder. The main objective here is to deepen your understanding about how the system works, and how interactions between key variables in the system influence the overall development trajectory. Photo: iStock.

One way to start is to work backwards from the aspirations, system benefits and dilemmas by asking ’why?’ Asking at least 5 ’why’ questions can often reveal a huge amount of detail about how a system works. For example, it is increasingly common that marine life gets trapped and killed by ghost nets. But why do fishers lose so many nets that then start drifting around? Why are fishers forced to go further out to sea where they are exposed to more intense storms? Why are middle men supplying fishers with credit to purchase more powerful boats allowing them to travel further out to sea? Why do economic benefits of illegal fishing flow from the local fishers to wealthy operators located in other countries?

Remember the Iceberg figure we talked about earlier in the introduction and in work card 8? This drilling down into the system is designed to get you to look past the ’surface’ issue (e.g. drift nets killing marine life) to discover the underlying dynamics (weak governance arrangements allowing wealthy external operators to exploit the local economic conditions). While it is tempting to jump to solutions, you should continue to drill down as far as you can. At this stage, it is important to really engage with the complexity of the system. It is important to recognise here that the process of drilling down and understanding complex systems is messy and at times overwhelming. Eventually however a clearer picture will start to emerge. Later on, once you have a good idea about which relationships are really structuring the system, you can revise and refine your systems model making it simpler by reducing it to the key variables and critical dynamics that will help you to identify leverage points for systemic change.

Locating the dilemmas in the overall system dynamics

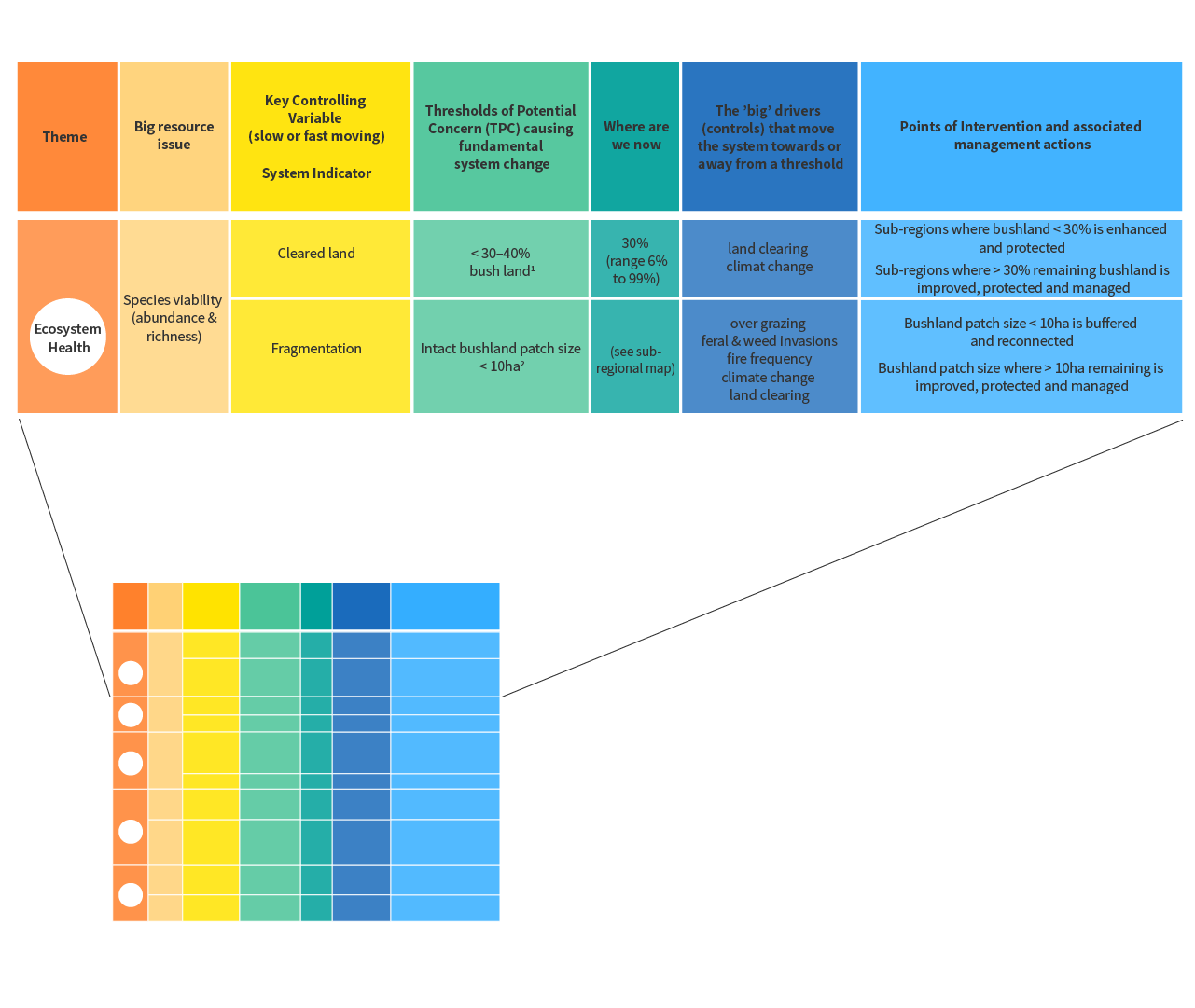

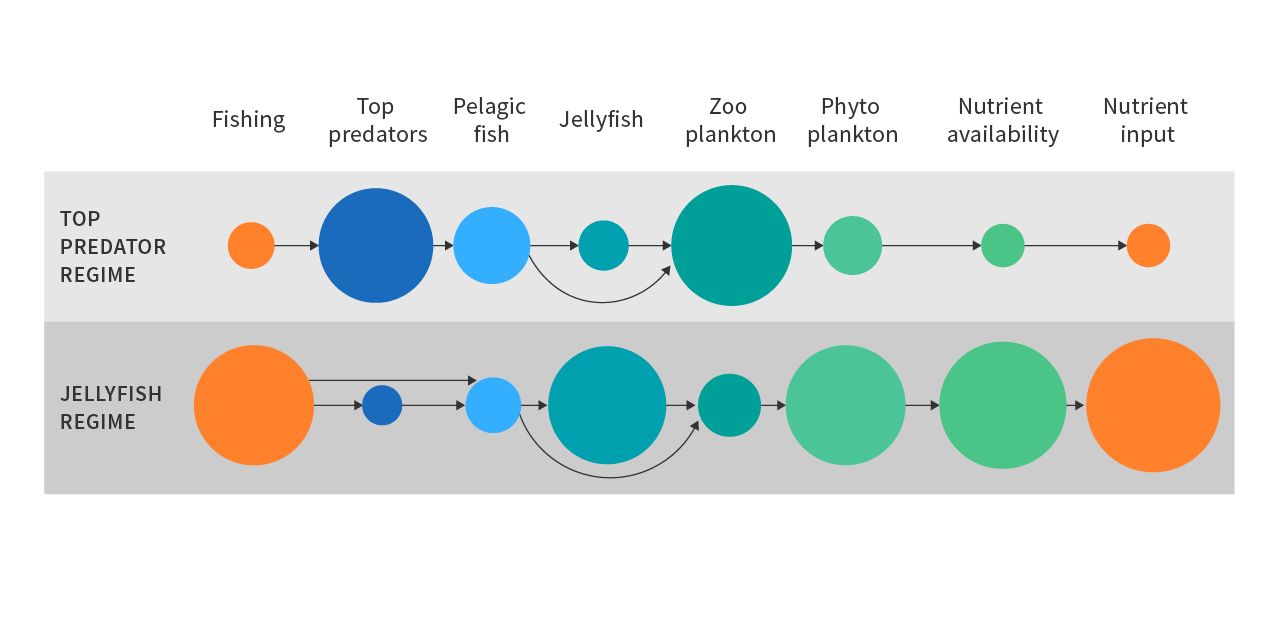

This deep exploration of dynamics should help you to ’locate’ the crux of the social-ecological dilemmas (figure 18.1), and also explain why the system generates a particular bundle of ecosystem services. Thus, the goal is to identify a smaller set of specific relationships between important system variables, given existing external drivers of change, that may explain the current state of affairs. A number of different tools can help you to approach this task.

- To explore how one key variable behaves in response to existing drivers of change (e.g. how availability of land declines in response to population growth), make a simple ‘behavior over time graph’

- To explore how a dependent variable changes in response to an independent variable (e.g. how crop yields decline in response to soil salinity), make a simple ’dependent/independent variable’ graphs

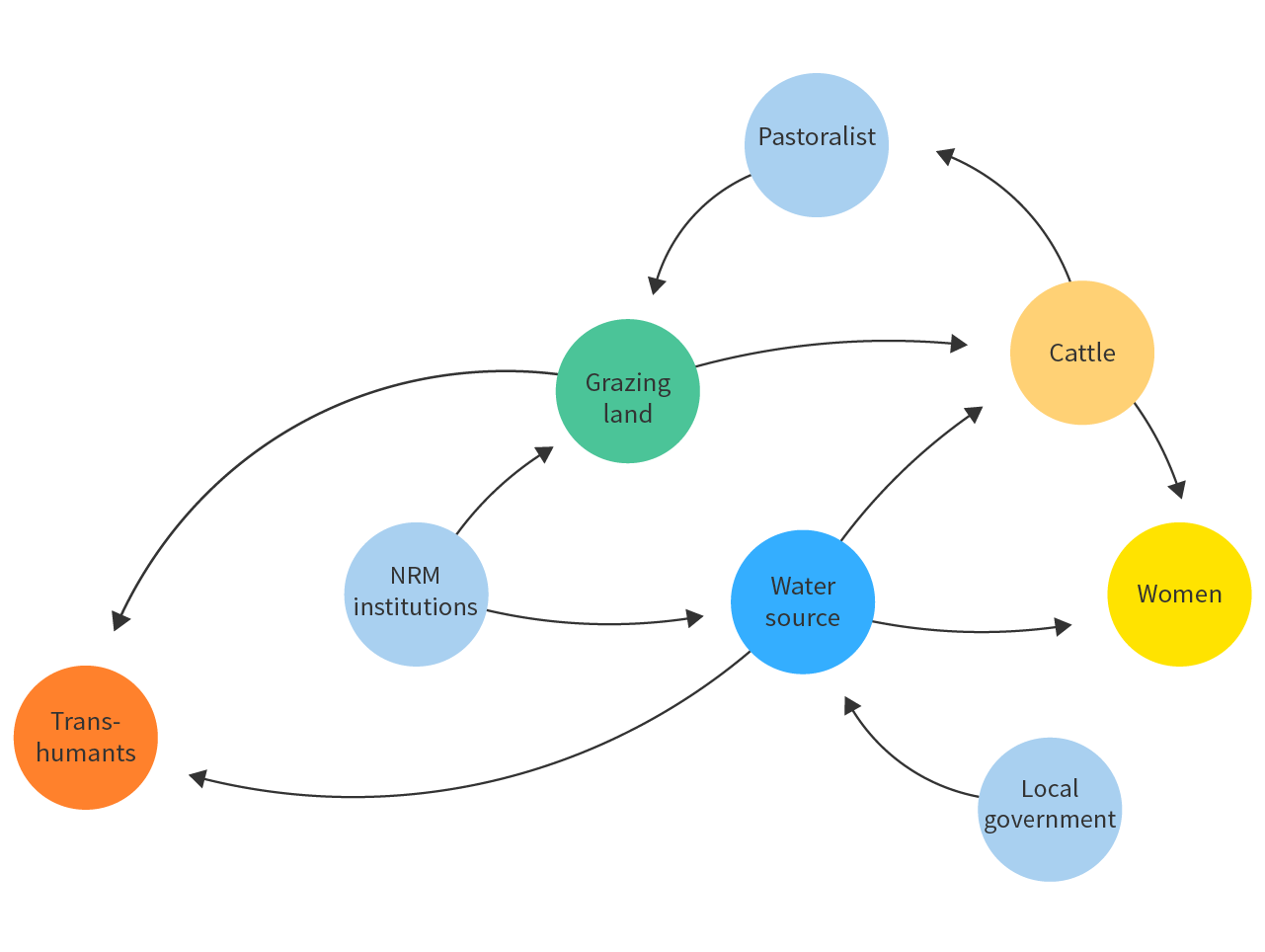

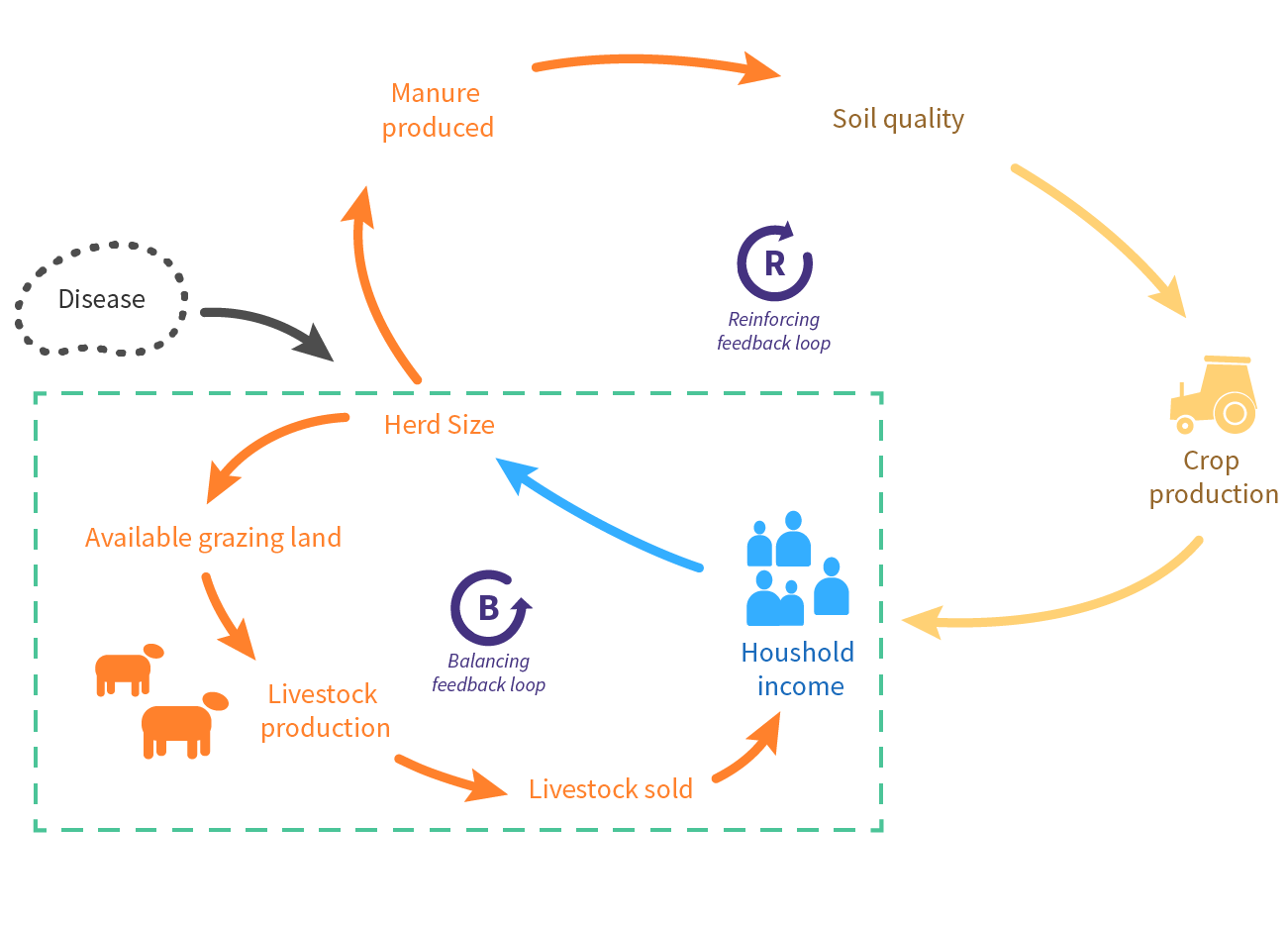

- To explore relationships between individual system components, make an influence diagram that links the variables together. See the attached case from the Wayfinder process in Senegal, illustrating how key components in the pastoral system link to each other.

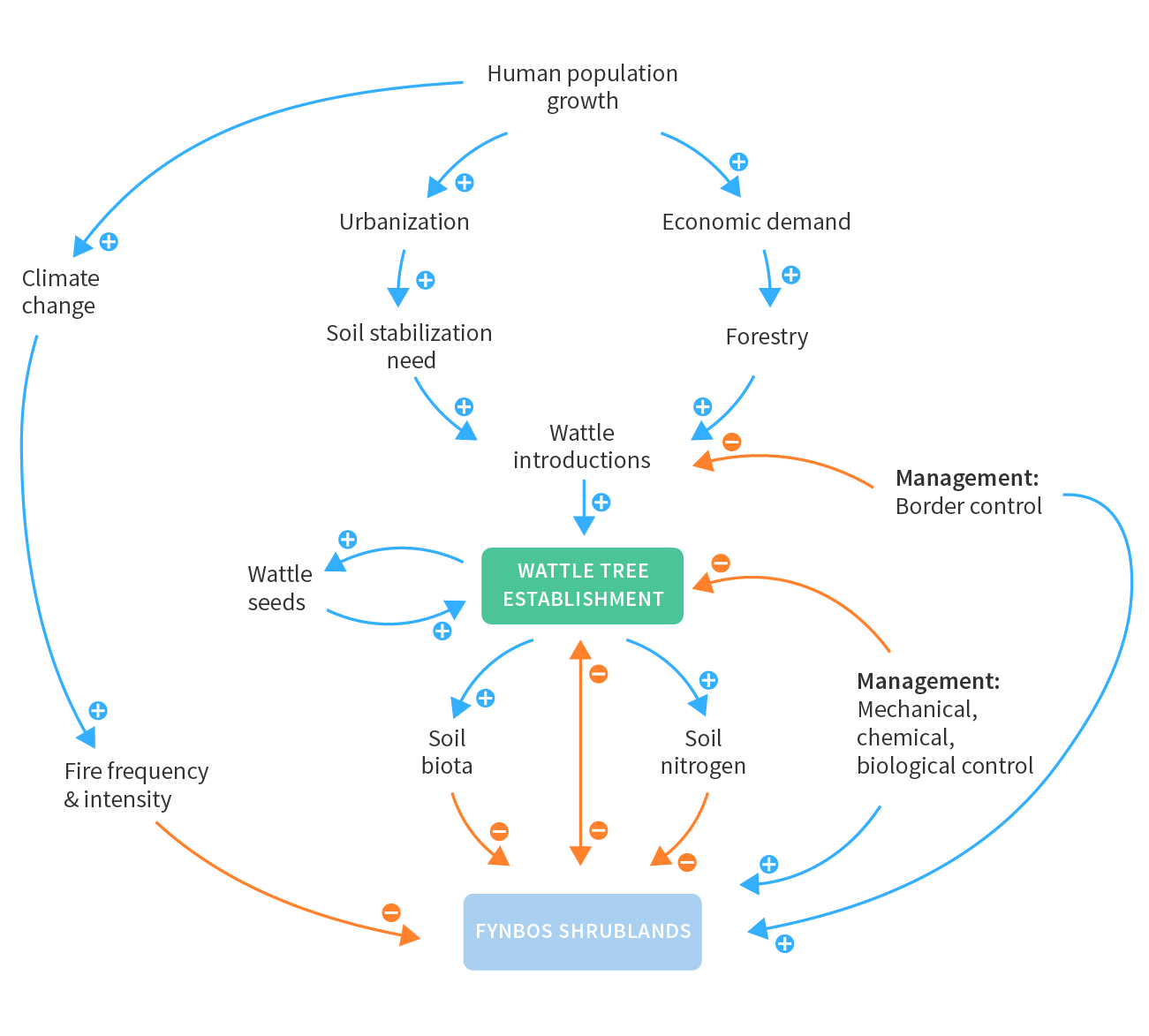

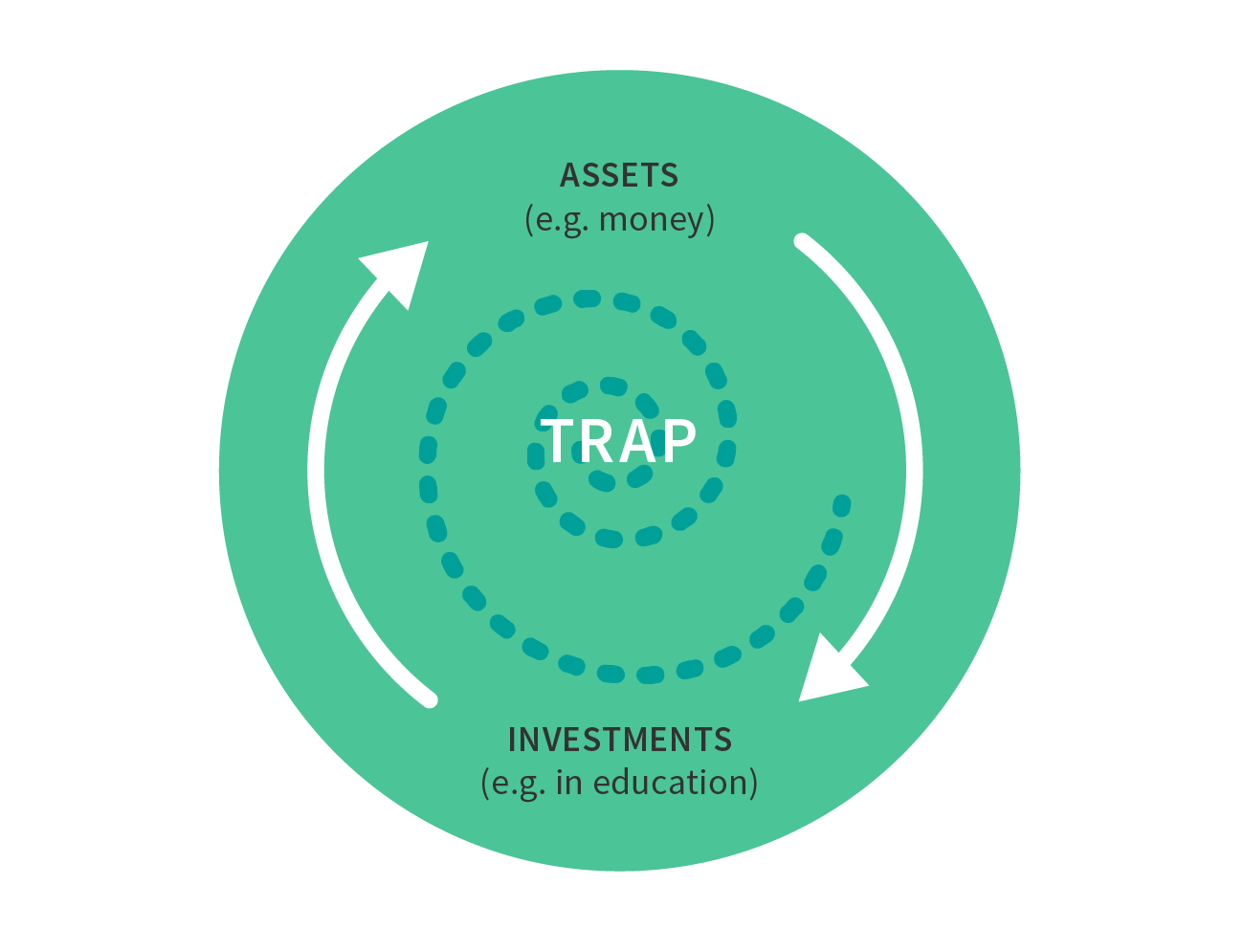

- To further explore interactions and feedbacks make a ’causal loop diagram’ (figure 18.1), that characterizes the different feedbacks as either reinforcing or balancing. For example, education and income levels are strongly linked through a positive feedback, whereas social cohesion and crime are also strongly linked but through a negative feedback, meaning that the higher the social cohesion the lower the crime rate is, and the lower crime rate the higher social cohesion. See the attached case from South Africa, which shows a causal loop diagram of a fynbos system that has become dominated by invasive Wattle.

Figure 18.1. A causal loop diagram highlights how key social, economic and ecological system variables interact, in response to existing external drivers and shocks. These interactions sometimes take the form of feedbacks, which may either have a reinforcing or a balancing impact on system behavior. Locating a social-ecological dilemma in the overall system dynamics is important to be able to design effective solutions. In this stylized agro-pastorlist example, the problems evolve around the lack of grazing land which hampers livestock production, which also has an impact on farmland management. Illustration: E.Wikander/Azote

Start qualitatively rather than quantitatively

When analyzing system dynamics, there is a tendency to look to quantitative models. We want to stress here that it is more important at this stage to identify the key variables and relationships between them, than to pursue a detailed quantitative model of a specific part of the system. Later on, quantitative models on specific system dynamics can be very useful to test hypotheses, but to start this analysis you may begin by simply drawing on a whiteboard or piece of butchers’ paper, preferably with key stakeholders involved. This process is often enough to generate a set of key insights about how the system works.

Keep in mind that you are exploring and learning, so you should feel free to play around with different approaches until you feel you gain a better understanding of how the system works, rather than trying to get it exactly right with one specific approach. The aim here is for you, your coalition and key stakeholders to rapidly gain new insights into key system dynamics. If something is not working, don’t persist with the same approach, instead try a different type of analysis, go up a level in complexity, change the starting point, come back to the issue later. or consult with someone else with a different perspective. It is also important to remember that while you have ’located’ or framed the social-ecological dilemmas in one way now, that may very well change later, as your understanding of system dynamics evolves.

Document assumptions and evidence

Underlying any model are assumptions. For example, in a system that relies on irrigated crops, there may be assumptions made regarding the amount of water available, the suitability of the type of crops being grown, or the market value of the crops. It is critical to be clear about whatever assumptions exist about the system and how this is represented in the model. They need to be articulated and critically reviewed using data and evidence where available. Where data or other evidence is not available, you may need to test your assumptions through small-scale experiments as part of implementation. Also, you should consider if there are there opportunities to learn about your assumptions from others or existing activities that are currently taking place in the system or similar systems elsewhere.

The models that you create will never be exact or fully correct. You should rather see them as a developing hypothesis based on your current understanding and the information and evidence that is available at the moment. This mindset is very important for being successful in phases 4 and 5 of Wayfinder.