Identifying where to intervene

The first task here is to identify where to intervene in the system. Leverage points are places in the system where a small intervention can have a large impact on the system’s behavior (figure 27.1). Outputs from Phase 3 such as influence diagrams, causal loop diagrams, behavior over time graphs, and descriptions of system dynamics, thresholds, traps, and cross-scale interactions etc. offer the clues to identifying leverage points.

Turning the lever. A leverage point is a place in the system dynamics whereby a small intervention gets a catalytic effect. To design effective strategies for change, you first need to identify where the levers are and then tailor actions that specifically target these points. Photo: iStock.

First consult your system models and look at key nodes and links in the system that have lots of interaction with other part of the system. Distill the model down so that it only includes the most critical components and dynamics. Look at key system feedbacks that influence how the system behaves as well as controlling or slow changing variables. Is the system locked-in by reinforcing feedbacks? For example, a coastal fishery that is experiencing steep declines in fish populations might zero in on high fishing pressure and the lack of off-limit areas that provide refuge to fish, leading some communities to consider establishing no-take areas. Alternatively, to address these dynamics, some communities might seek to diversify their livelihood options by re-envisioning their community as one supported by both fisheries and tourism.

Figure 27.1. Interventions in the system should target leverage points (green), which are key relationships in a social-ecological system, where by a smaller change can have substantial impact due to the change in system dynamics. Illustration: E.Wikander/Azote

Different kinds of leverage points

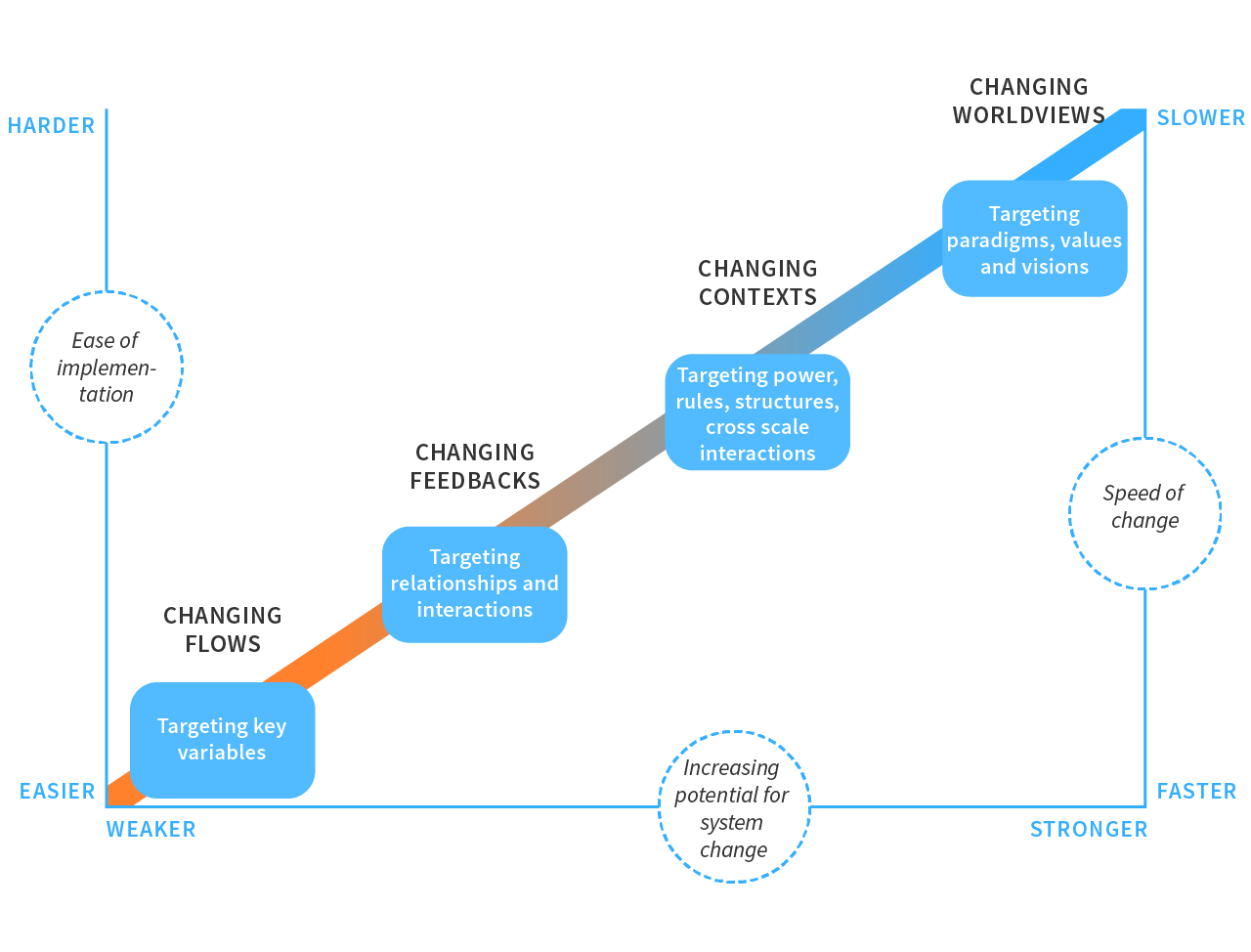

It is important to realize that not all leverage points are equal. Figure 27.2 shows how ease of implementation, the potential for system change, and the speed of system change varies along a gradient of different types of leverage points, which can be conceptualized as ranging from flows, to feedbacks, to contexts to world views. For example, in an intensive agricultural system, lowering the levels of chemical pesticides applied is essentially changing a flow, whereas a more profound change in land management that would eliminate the need for pesticides would reflect a change in system feedbacks. Changing the contexts for this type of intensive agriculture, could for example be done by changing how EU’s Common Agricultural Policy works, and changing world views could reflect a more far-reaching change of public opinion relating to organic versus non-organic produce. Changing values and world views is considered to be the most powerful type of leverage point, but also the most difficult to influence. When compiling your initial list of actions, think about ways of striking a balance with easier and more challenging levers. See attached activity sheet.

Figure 27.2. Different types of leverage points have different potential for system change, but generally also different ease of implementation and speed of change. Illustration: E.Wikander/Azote

Identifying what to do

Once you have identified where to intervene in the system, the next issue is what to do. First brainstorm around possible actions that target the leverage points and move the system towards your goal. It may also be useful to think about actions that help the system avoid undesirable futures (consult scenarios). You should think of actions broadly. They could include a range of different things, for example changes in 1) technology and management practices, 2) formal institutions, such as laws or regulatory frameworks, 3) economic incentives, such as subsidies or taxes, 4) networks and connections, e.g. diffusion of new technology or information access, or 5) awareness levels, education, behavior, values, and norms.

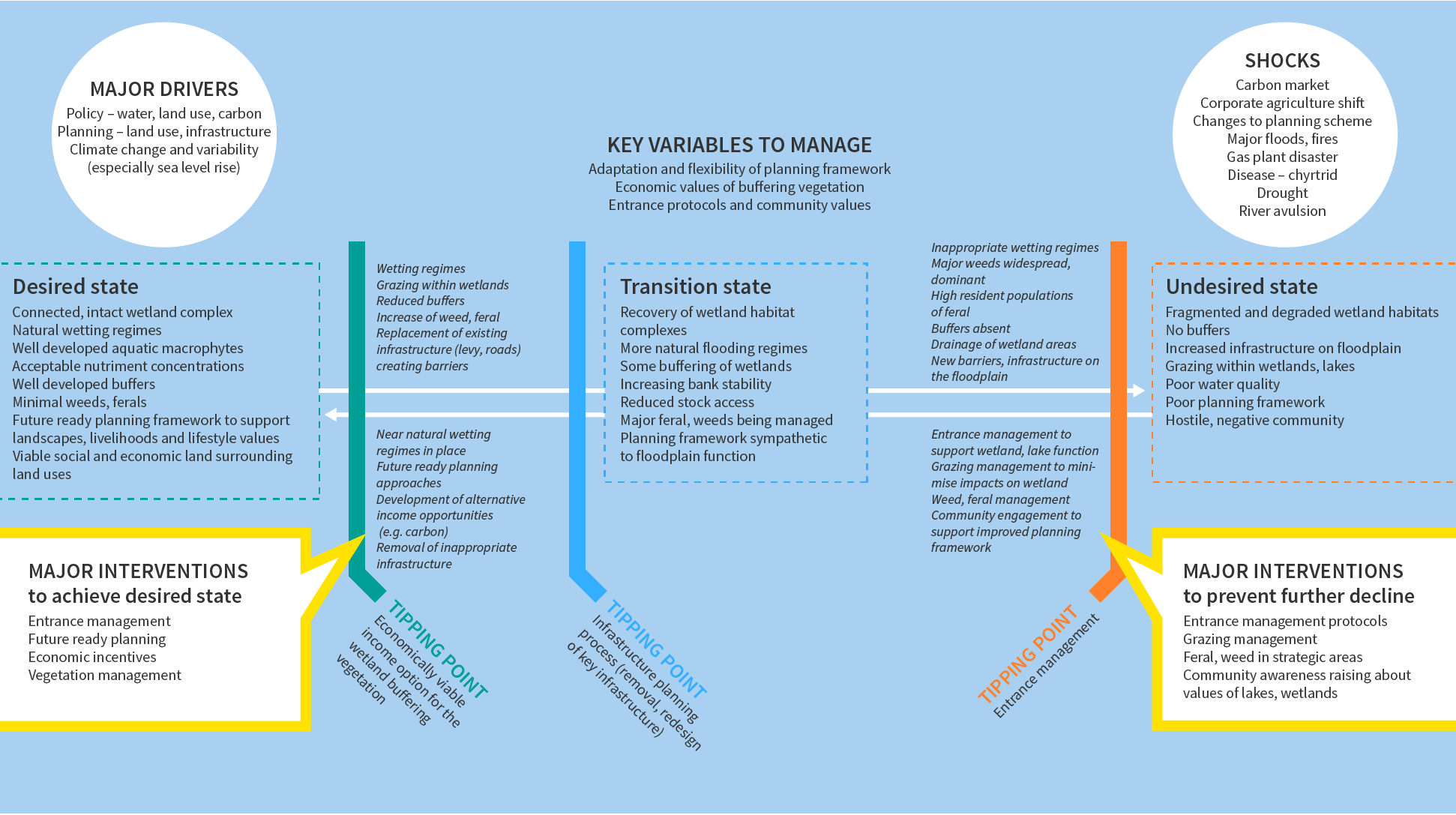

Keep in mind you are trying to target specific points in the system. Therefore, generic actions such as ‘working with local municipal staff’ or ‘building capacity’ are not sufficiently detailed. At this stage, the more detailed you can be, the better. See the attached case from the Snowy River wetland system in Australia, where they designed actions that specifically targeted tipping points.

Document evidence and assumptions as you compile your list of actions

Upon compiling your initial list of actions that target the leverage points, ask yourself why you think these will work? It is important to document the evidence and assumptions regarding how these actions might change the system. This information will form the basis for the learning-by-doing approach to implementation that is developed in Phase 5. If you cannot clearly explain why you think your actions will work, you may not have a clear enough understanding of how the system works. In that case, you should revisit previous steps to gain this understanding before proceeding. The attached discussion guide helps you structure the work on actions that target leverage points in the system.